[Evil Code #001] file scope goto statements

Prologue: sizeof and arrays.

Like most shitty AI startup ideas, our story starts with a couple college students having lunch together. Obviously, since we are all very normal people, we were doing what normal humans do over lunch: Discussing what we think a particular piece of C code will do. Specifically, the other two people with me are taking their first C programming class, and were slightly confused about how sizeof works. So, we constructed the following piece of code to base our discussion on:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

// for the nerds out there, for this discussion, we assume a 64bit system

// where sizeof(int) == 4 and sizeof(size_t) == 8

int arr[5] = {0,1,42,69,420};

printf("%ld\n", sizeof(arr));

return 0;

}

Now, at first glance, it might seem obvious: Of course it prints 5. But if you are slightly more familiar with C code, you might instead say 20 (array of 5 int values, each one taking up 4 bytes, for a total of 20 bytes).

I, of course, did none of those. In my infinite wisdom, thinking I was so very clever (spoiler: I am not), say that “Uhmm actually, it will output 8”. Now, what could possibly lead me to say such a thing, you might ask? Well, if you have written C before, you might remember that the name of an array type (that is, its identifier) evaluates to a pointer to its first element. So my logic was that since pointers are just a number stored in the data type size_t, we should have that

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

int arr[5] = {0,1,42,60,420};

//arr is an expression that evaluates to a pointer to the first address,

int* ptr = arr;

//meaning we should expect these to match, right?

printf("%ld = %ld\n", sizeof(ptr), sizeof(arr));

return 0;

}

Sounds reasonable, doesn’t it? Thats what we all thought. So, we do what we could have done about 30 minutes before and run the code in a actual machine instead of trying to run it in our heads.

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$ gcc -c test.c

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$ gcc -o test test.o

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$ ./test

8 = 20

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$

What the hell.

Actually before that, mandatory nitpick intermission: This has to be the most convoluted way of compiling a single .c file that I have ever seen. I take no responsibility for that. With that out of the way, we can go back to our regularly schedulued

What the hell. How is this possible? How can it be that ptr = arr, but sizeof(ptr) != sizeof(arr)? It seems that the two statements are fundamentally at odds: After all, two things that are equal can’t possibly have a different size, right?

Chapter 1: Expressions

As it usually turns out, the devil is in the details. I was absolutely right when I said:

The name of an array type (that is, its identifier) evaluates to a pointer to its first element.

The keyword being evaluates. In C (and most programming languages), when the compiler sees a name (usually called identifier), it treats that as an expression: That is, it treats it as something that needs to be replaced by something else (usually a value in memory). For example:

// declare a variable, with type "int" and identifier "x" that stores the value 5

int x = 5;

// declare a variable, with type "int" and identidier "y" that stores whatever the expression "x" evaluates to.

// since an expression with an variable identifier in it evaluates to to the variables value, we get

// y = 5.

int y = x;

This seems to be an unecessaryly convoluted distinction: why do we care if the compiler goes through this “extra step” of “evaluating an expression” if it gets the same end result? Well, because language designers are some of the most clever people out there (Well, considering java script is a thing, maybe I should say language designers are think themselves to be some of the mose clever people out there). They realized is that since everything in the C language has a type, and that type is always known before we even compile to program (must be explictly stated in code).

And since every type has a fixed size depending only on the machine the code will run in (which must be known at compile time, since compilation is different for different machines), there is no reason to waste precious CPU cycles evaluating that expression every time the code runs. Instead, at compile time, when the compiler is going throught your code, it will simply look at the expression inside sizeof() and decide its data type, without actually evaluating it. Since this is done at compile time, the value of sizeof can simply be hardcoded in the binary executable, saving instructions each time the code runs.

If you aren’t convinced by a wall of text with no sources, you aren’t alone. Which is why to convince you (and my friends), I put together the following experiment:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

int x = 0;

// x++ is a expression that, when evaluated, returns the current value of x,

// and then increases x by 1.

printf("sizeof(x) = %ld\n", sizeof(x++));

// so if x++ truly was evaluated, we should have x=1 starting in this line of code.

printf("x = %d\n", x);

return 0;

}

And ran it on my friends computer (with non disgusting compiler commands this time thank you very much)

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$ gcc test.c

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$ gcc ./a.out

sizeof(x) = 4

x = 0

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$

Which proves my point: x++ is never evaluated, as otherwise, we would have x = 1. This explains why our logic failed before: We assumed arr would be evaluated, resulting in a pointer to the first element, which does have size 8. Since this is not the case, sizeof acts on whatever type arr is, and not on a pointer. But hold on a minute: This seems to imply that arrays in C are not pointers (unlike what half the internet would have you believe). But I have also told you everything in C has a data type, so what is the type of arr?

Chapter 2: Derived types and their size.

As it turns out, C has a little something called derived types. Derived types are types obtained by combining primitive data types in some creative way: That is, they are not new types per say, but one of the primitive data types being used in a clever way. For example: in 64 bit systems, the data type int* is just an long, in the sense they are both 64bit integer types. But when I write int* im telling my code to interpret the value of that “long” differently: Its not just some number, its a number with meaning attached to it. In the case of int*, its a number representing the memory address of the first byte of an int. We can prove our claim pretty easily, with the code below.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

// I can only promise you this works in a 64bit linux system. Windows should still work

// but I don't use bad OSes, so I can't test it myself.

int x = 5;

long ptr = (long)&x;

printf("*ptr = %d\n", *(int*)ptr);

return 0;

}

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ gcc long_ptr.c

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ ./a.out

*ptr = 5

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$

Similary, array types are also a derived type. When one writes int arr[5], this is simply telling the compiler “I want 5 int types to be stored right next to each other in memory”. Since we know how big each int is, as long as you know where the first byte of arr is, you can figure out where in memory each int is, and retrieve it as needed.

This also hints at what sizeof is doing: Since a derived type, by definition, is a clever arrangement of primitive types, there is some formula involving only sizeof primitive types and maybe some constants that gives the correct size of a derived type. For pointers, this is simply a clever #define macro located in the standard header <stddefs.h> which decides which of the primitive types is large enough to be used asthe pointer type. For arrays, this is simply

Where len is the length of the array (given inside [] at declaration) and type is the data type of each element in the array. This is where we parted ways, since all of us had classes to get to. With a seemingly satisfactory answer to our original pradox. We could have been done, put an end to this madness, but no. We just had to try one more thing.

Chapter 3: Variable Length Arrays (VLAs)

VLAs were an attempt by the C language to bridge the gap between fully dynamic arrays and fully static arrays: They let us have an array with unknown size at compile time (but with a well defined expression for the size), but fixed size during execution (in the sense after the initial declaration, it cannot change size). Translating this jargon into code, it means we can do things like this:

#include <stdio.h>

void foo(int a)

{

// the size of arr is always well defined once we get to this line

// of code: It's given by the expression sizeof(int) * a

// unlike before however, the exact value cannot be pre computed at compile time.

int arr[a];

printf("sizeof(arr) = %ld\n", sizeof(arr));

return;

}

int main(void)

{

int a;

scanf("%d", &a);

foo(a);

return 0;

}

Like the code comments indicate, it is literally impossible for the compiler to know the size of arr at compile time. But the expression that gives that size is constant and well defined: it must be

a * sizeof(int). So instead of hardcoding it in the binary file, it will instead hardcode the expression a * sizeof(int), which makes sense. We were about to leave, content with our answers, when a fourth friend walked in. He asked what we were working on, and we brought him up to speed (while he averaged a couple “what”s and “bruh”s per minute). But like us, he seemed pretty convinced by our conclusions. As we were about to leave, he has one last question for us.

What happens if we put a negative number?

Now, this might seem silly. Absurd even. We all know C doesn’t allow you to define negative length static arrays. Surely there is some sort of validation when creating a VLA. Surely we will segfault, right? Or at the very least, the value is implictly converted to a unsigned int. There is no way the C programming language will let us do something obviously wrong.

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$ gcc test.c

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$ ./a.out

-1

sizeof(arr) = -8

friend1@cs.university.edu:~/cs314/bruh$

At this point, my friends must have sensed the evil scientist in me waking up (and by extension, a solid chunk of their day about to evaporate into C code) because they all left for their classes (which I totally didn’t have to go to. Nope. I would never skip lecture to obssess over a piece of insignificant C code). Who am I kidding, I have the self control of a lobotomized ant. So instead of attending physics, I turn my attention back to the code. My first question is what happens if I try to index into this array? Does it even work? To answer that, we will consider the following code:

#include <stdio.h>

// for the nerds, from this point on this is being run on my own laptop,

// a framework 16 with fedora linux on it. On this machine, sizeof(int) == 4,

// sizeof(int*) == 8. This is a 64bit machine.

void foo(int a)

{

int arr[a];

printf("sizeof(arr) = %ld\n", sizeof(arr));

printf("arr[0] = %d\n", 0[arr]);

return;

}

int main(void)

{

int a;

scanf("%d", &a);

foo(a);

return 0;

}

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ gcc main.c

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ ./a.out

-2

sizeof(arr) = -8

arr[0] = 0

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$

I wonder… how low can we go?

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ ./a.out

-10

sizeof(arr) = -40

arr[0] = -2086110960

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ ./a.out

-15

sizeof(arr) = -60

arr[0] = 0

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ ./a.out

-20

sizeof(arr) = -80

arr[0] = -1927853840

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$

Not that low, apparently. We segfault at -20. This was bound to happen eventually, theres no way allocating negative length arrays was ever going to go right. Let’s try and find what value, exactly, we start segfaulting at.

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ ./a.out

-16

sizeof(arr) = -64

arr[0] = 0

No, the above is not a typo. At -16 the program neither terminates normally nor does it segfault: It just hangs as if in a infinite loop. This seems to be stable (ie: no additional corruption seems to happen overtime, as I left my computer on overnight running it and it was still going in the morning, until I ctr^c out of it).

^C

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$

What the fuck.

Part 4: The call stack

Have you ever wondered how functions work? How does a function “know” where to return to when it is done? How are the parameters actually passed between functions? Is it some sort of network shenanigans? Black magic? Maybe owls with letters?

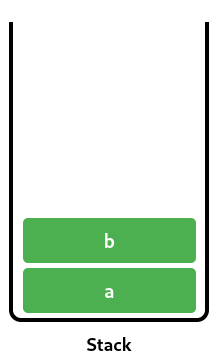

Unsurprisingly, none of the above. The actualy answer is the call stack. Imagine you have a function called foo. Suppose that foo has two local variables a and b. We can imagine these variables as living in a part of memory associated with foo (or more specifically, with the current call of foo). This is called foos stack frame, and it looks something like this:

Obviously, your program (or your function) are not the only thing living on the computers RAM (where the stack is located). So, we need some way of knowing where foos stack frame starts and ends. This is the job of two registers (or pointers) called rsp and rbp. rbp always points to the bottom of the stack frame (ie: where the stack frame begins) and rsp points to the top of the stack (ie: where it ends). Clearly, with that information, and knowing the size of each type in bytes, we can access any local variable of foo as a offset from rbp, which is exactly what the compiler does.

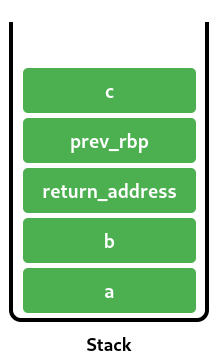

Sounds reasonable so far, right? So now the question becomes what happens when we call a function from inside foo. In particular, assume we call a function bar from inside of foo. Where is bars stack frame generated? And how does bar know where to return to? The answer to both of these questions turns out to be surprinsgly simple: When foo calls bar, it pushes a new value to the stack: the return address (think of it as the line of code that needs to be executed in foo right after bar is done running). Then, we simply create bars stackframe right after foos stack frame ends. This is done in two steps:

- we push the current value of

rbpto the stack (because we need that later, when we return to foo), - and then we set

rsptorbp(creating a 0wide stack frame for bar, right on top of foos frame).

Obviously, rsp wont stay equal to rbp: as soon as bar wants to store a local, it will move just like before. So, if bar has a local variable called c, the stack now looks like:

And when bar finishes executing, it can cleanly resume the execution of foo by:

- cleaning up after itself (aka: popping all its local variables away, which is equivalent to setting

rsp=rbp) - restoring the previous stack frame, by setting

rsp=rbp, and then poppingprev_rspfrom the stack, intorsp - and then setting the “instruction pointer” (read: line to be executed) to be

return_addresswhich we get by popping the first thing in the stack.

Which lets foo resume execution as normal. (Disclaimer: This was an extremely oversimplified explanation: there’s a lot of nuance going on here, especially with how the stack actually grows downwards. Don’t worry about this too much, all you need to know is in reality, the “top” of the stack is the lowest memory address on it).

We finally have all we need to explain the behavior of our code. The first key evidence is our negative sized VLA. Remember how I just said that the stack allocates space for local variables (including our little VLA) by offsetting rsp by whatever the size of the local variable is? Well, with a integer VLA of size a, this size will be given by sizeof(int) * a, meaning we have rsp -= sizeof(int)*a (the - is because the stack grows downwards. Again, don’t worry about it too much). Which sounds fine… until we ask what happens if a is negative. If that happens, we instead have: rsp += sizeof(int) * |a| where |a| is the absolute value of a. It should be pretty clear there is no way this can lead to good things: We just shrunk the size of the stack frame instead of growing it to accomodate our local!

In fact, if we “shrink” it by enough, we might end up with what I like to call a pointer inversion: If a is large enough, we might have that rsp becomes greater than rbp (stack frame ends before its starts????). Now, this by itself doesnt cause problems… yet. But it sets the stage for the second part of our trick: The printf function call.

When printf is called, it goes through the same process we described for our toy functions: we set rbp = rsp and start a new stack frame right below the end of the previous one. But now, since rsp is located somehwere it really shouldnt be (before rbp), this means the new stack frame we create overwrites part (or all) of the stack frame of foo. In particular, this new stackframe, somewhere inside of it, contains the return_address that foo will need later. Meaning that when printf is done and returns, it cleans after itself, deleting its stack frame… which also deletes the value we needed. Meaning foo now doesn’t know where to return to when its done, and our program just hangs forever. Amazing.

But seeing is believing, so I have prepared some demonstrations for you. The first is quite tame: It’s simply a sanity check for our theory. The claim we made is the issue boils down to a function call being done inside foo. So, if we are remotely right, removing function calls from foo should stop the behavior. We consider the code:

#include <stdio.h>

// for the nerds, from this point on this is being run on my own laptop,

// a framework 16 with fedora linux on it. On this machine, sizeof(int) == 4,

// sizeof(int*) == 8. This is a 64bit machine.

int dummy[10];

void foo(int a)

{

int arr[a];

dummy[0]=a;

return;

}

int main(void)

{

int a;

scanf("%d", &a);

foo(a);

printf("dummy[0] = %d\n", dummy[0]);

return 0;

}

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ gcc bruh.c

-16

dummy[0] = -16

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$

As expected, our program does not hang and terminates normally. Our second example is much more interesting (in fact, it is the namesake of this post):

#include <stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

// for the nerds, from this point on this is being run on my own laptop,

// a framework 16 with fedora linux on it. On this machine, sizeof(int) == 4,

// sizeof(int*) == 8. This is a 64bit machine.

long bruh;

int dummy[10]; // I need to fool the cmpiler

void bar(long a)

{

dummy[0] = a;

return;

}

void foo(int a)

{

int arr[a];

bar(arr[0]); // this function call breaks the stack

*((long*)(((char*)(void*)&arr[0])-8)) = bruh; //evil memory hack -> manually fix the return_address

//after bar deletes it

return;

}

int main(void)

{

int a;

bruh = (long)&main; //surprise tool that will help us later!

bruh+=110; //magic offset

scanf("%d", &a);

foo(a);

printf("dummy[0] = %d\n", dummy[0]);

if(dummy[0] == 0)return 0;

printf("dummy[0]ooo = %d\n", dummy[0]);

printf("what the...\n");

exit(0);

return 0;

}

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ gcc main.c

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ ./a.out

-16

dummy[0]ooo = 0;

what the...

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$

Think about what just happenned above: On one hand, it seems like dummy[0] is 0. On the other hand, that would mean the line printf(“what the…”) is unreachable. And yet, here we are. Further, it lookks like we also skipped the line printf(“dummy[0] = %d”, dummy[0]);

In other words, we just made a very very shitty filed scoped goto statement.

And like any good mad scientist, once we find a new trick, there is only one reasonable response: We make a proof of concept demonstrating everything we know about it. Putting everything we learned so far together, I came up with what is likely to be one of the more cursed ways of computing the first n fibonnaci numbers.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

// globals are bad code standard, but honestly,

// that is the least of your concerns with this code.

// (also, as you will see, we cant trust locals in this code)

long curr_fib=1,d=1,next_fib=1,counter=0,last_fib=0;

void goblin(){}

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

last_fib = last_fib ? last_fib : atoi(argv[1]); //a is for atoi

d=1; //flag / temporary var, dont worry

long b = curr_fib;

curr_fib = -1;

long e[curr_fib]; // dont worry about it

curr_fib = b;

goblin(); // :)

if(d) e[9] = e[-1]; //evil memory trick

//exits if reached the requested fib number

// or if next_fib overflew into negatives.

if(next_fib < 0 || last_fib <= counter) exit(0);

printf("%ld\n", curr_fib);

// standard fibonnaci stuff

d = next_fib;

next_fib = next_fib + curr_fib;

curr_fib = d;

d = 0;

counter++;

return argc; // =)

}

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ gcc fib.c

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$ gcc ./a.out 10

1

1

2

3

5

8

13

21

34

55

carvalj@earth:/mnt/shared/exploring/vla_bad$

Ps: This will only run in x86_64 linux. I have however, tested it under QEMU and it runs, so feel free to run it with QEMU for yourself. In particular, try removing the “useless function call” and seeing what happens.